Legalize Joyce!

- Charles Arrowsmith

- Aug 13, 2014

- 5 min read

A June day in Dublin would be a fractal of Western civilization. – Kevin Birmingham

Kevin Birmingham‘s splendid first book is so packed with smut hounds, tortured geniuses, anarchists, and iconoclasts that it’s hard to pinpoint where its greatest pleasures lie. Although ostensibly an account of the publication ordeal and legal furore surrounding one of the twentieth century’s greatest novels, The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses casts a much wider net. As in Kevin Jackson’s excellent Constellation of Genius (reviewed here), there’s literary gossip aplenty. We first see one of its main characters, Ezra Pound, teaching W.B. Yeats to fence. Later, Ernest Hemingway teaches Pound to box and meets Joyce. The great Joyce, unable to see an assailant in a barroom quarrel, would instruct his rambunctious young friend, “Deal with him, Hemingway! Deal with him!”

From a present-day perspective, it’s also a valuable reminder of where we were, culturally, a mere century ago. “All the secret sewers of vice are canalized in its flood of unimaginable thoughts, images and pornographic words,” wrote one of Ulysses‘s earliest reviewers, in London’s Sunday Express. Powerful censorship bodies on both sides of the Atlantic agreed, and between its publication date, on Joyce’s fortieth birthday in 1922, and its widespread legal availability in the US and the UK, fourteen years passed. Ironically, the first legal ruling in its favour — written by the American Judge Woolsey in 1933 — reads more like literary criticism than legal judgment:

Joyce has attempted — it seems to me, with astonishing success — to show how the screen of consciousness with its ever-shifting kaleidoscopic impressions carries, as it were on a plastic palimpsest, not only what is in the focus of each man’s observation of the actual things about him, but also in a penumbral zone some residua of past impressions, some recent and some drawn up by association from the domain of the subconscious.

This, though, is rather apt, for one of the most persuasive aspects of Birmingham’s book is its notion that Ulysses “changed not only the course of literature in the century that followed, but the very definition of literature in the eyes of the law.” A new legal definition of obscenity was required for this to happen, and sensitivity to art was essential to that.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Birmingham’s marvellously told story begins with the artist as a young boy. As a child, Joyce lived at eleven addresses in ten years, a nomadic pattern he would continue throughout his life. (This was no doubt how, as Birmingham suggests, he came to know Dublin so well.) At the Royal University, he proved to be a controversial student: an essay he wrote on the Irish Literary Theatre was effectively banned when he was just nineteen. His medical ambitions proved brief; instead, he eloped to the Continent with Nora Barnacle, a scarcely educated woman with whom he fell in love and asked, by way of securing her loyalties, “Is there one who understands me?” And the date of their first meeting? June 16, 1904, perhaps the most significant in twentieth-century literature.

Their life together — in Trieste, Zurich, and Paris — was not an easy one. Joyce was troubled throughout his life by acute iritis, a condition that caused him almost unendurable pain and led to many gruesome ocular surgeries (the squeamish may need to skip page 101). His writing was no bacon-winner either. Despite accruing an incredible list of admirers — Pound, H.G. Wells, H.L. Mencken, and later T.S. Eliot — Joyce was plagued by censorship problems during the publications of Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, while the serialization of Ulysses in a New York magazine caused all manner of chaos.

Birmingham sustains several parallel narratives throughout The Most Dangerous Book, among them the history of censorship in the US. Vice suppression in America was particularly dogged. “You must hunt these men as you hunt rats,” declared Anthony Comstock, the principal upholder of standards from 1872 until his death in 1915; “without mercy.” Under the Comstock Act of 1873, post offices in the US were empowered to seize, inspect, even burn material they deemed obscene. The delicate sensibilities of the American public were thus sheltered from, by Comstock’s count, almost three million obscene pictures, fifty tons of books, and 318,336 “obscene rubber articles.” His successor, John Sumner, chosen to head up the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1915, was equally dogmatic, and it was during his tenure that Ulysses reared its Cerberean head(s).

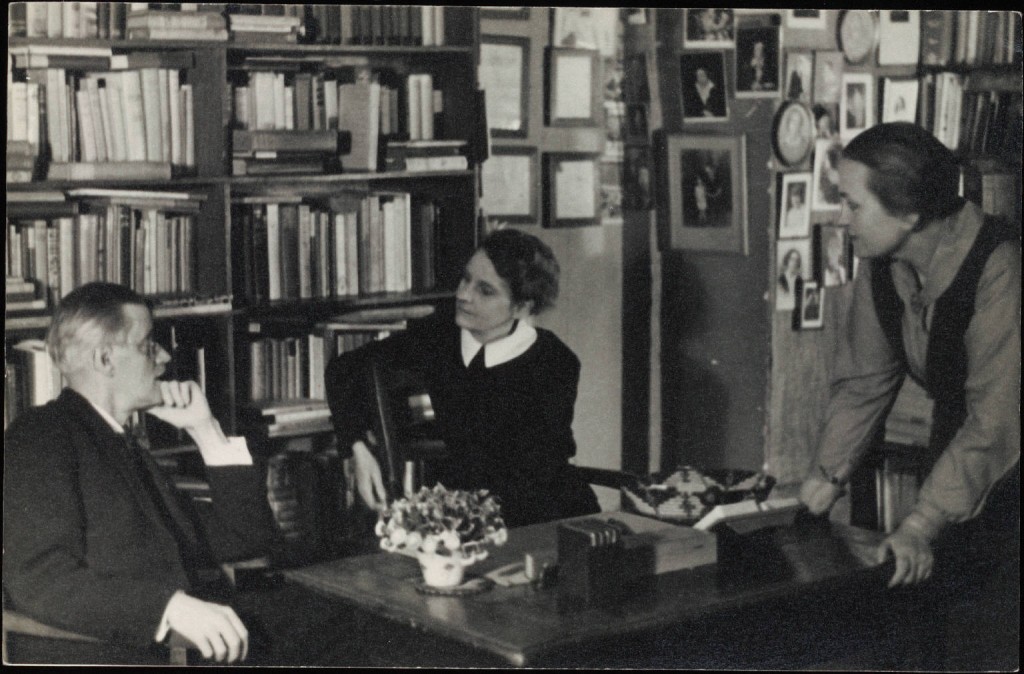

One of the great services Birmingham performs with his book is to bring to the fore the geographically disparate but courageous women who between them midwifed Joyce’s novel. There’s Harriet Weaver, the cotton heiress who printed A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in her magazine The Egoist, and whose endowments to Joyce by 1923, which sustained him and his family during the writing of his epic, totalled the equivalent of more than £1 million in today’s money. On the American side, there’s the tenacious duo of Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, whose avant-garde periodical The Little Review was ultimately prosecuted for its serialization of Ulysses in the wake of the “Nausicaa” episode. Finally, there’s Sylvia Beach, the founder of legendary Parisian bookstore Shakespeare and Company, who published the first full edition of Ulysses in 1922. By that stage, portions of the manuscript had been burned (by a horrified British diplomat), “Nausicaa” had been convicted of obscenity in New York, and copies of the book, in Birmingham’s potent phrase, “lay stacked like dynamite in a revolutionary cellar” beneath Beach’s shop.

It’s a virtuosic piece of research. Alongside the principal cast we meet the patient Maurice Darantière, who was set the task of typesetting the ever-changing and scarcely legible manuscript as Joyce’s final edits were telegraphed in. Later we’re introduced to the magnificently named Barnet Braverman, a one-time anarchist ready to “put one over on the Republic and its Methodist smut hounds” by smuggling copies of the book from Canada into the US. Then there’s Samuel Roth, the enthusiastic but amoral publisher whose pirated Ulysses formed the accidental basis for Random House’s first official US edition. Finally, we meet Morris Ernst, the civil liberties lawyer whose arguments in favour of Joyce’s epic as a “modern classic” not only secured its legalization but brought literature under the purview of First Amendment cases.

Birmingham’s eye for the telling detail and brilliant quote; his ability to sustain complex narratives across continents and disciplines; his perspicuous observations on everything from “dirty words” to Joyce’s feelings of guilt over his syphilitic blindness, not to mention the literary merits of his astonishing work — all add up to a quite marvellous account. It ranks alongside Constellation of Genius as one of the best books in recent years about the ruptures and inspirations of modernism during its troubled birth.

When Ulysses was finally published in the US by Random House, Joyce appeared on the cover of the January 29, 1934, edition of Time magazine, and it’s with their words I close:

Watchers of the U.S. skies last week reported no comet or other celestial portent. In Manhattan no showers of ticker-tape blossomed from Broadway office windows, no welcoming committee packed the steps of City Hall…. Yet many a wide-awake modern-minded citizen knew he had seen literary history pass another milestone. For last week a much-enduring traveler, world-famed but long an outcast, landed safe and sound on U.S. shores. His name was Ulysses.

The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle Over James Joyce’s Ulysses | Kevin Birmingham | NY: The Penguin Press, 2014 (432pp)

First published on August 13, 2014, by House of SpeakEasy.

Comments